Nature sightings in MDIS – The oriental pied hornbills

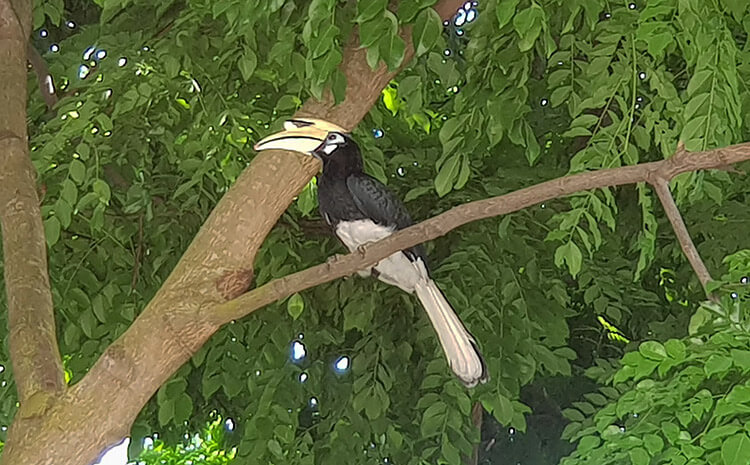

“Hey, there’s a big bird on the tree!” – I heard a student cry out to her friend as I was walking past block F in the MDIS campus. I looked up and there it was; on the tree sat a majestic looking bird with a large curved bill, about half a meter tall, clad in monochrome plumage. The students started discussing among themselves what kind of bird that was – a toucan? A hornbill?

In fact, it is not uncommon to see these winged visitors on MDIS grounds. Yes, I’m referring to the hornbills; they either come alone or as a flock of up to 4 members. Sometimes they rest on lamp posts, or on tree branches behind block E and around block F. When sighted, students and staffs would quickly whip out their smart phones to take pictures of these spectacular birds.

I remember that my first encounter with hornbills was at Pulau Ubin a few years back; I did not think I would see them in the central ‘urbanised’ part of the main island. I googled and found out that what we see now is the fruits of a successful wildlife rehabilitation effort that begin in the early 2000s – Singapore Hornbill Project and the subsequent hornbill breeding programme. These conservation projects are especially important for endangered species such as the hornbills that were once absent from our shores for about a hundred years, only to be spotted again in Pulau Ubin in the 1990s.

The oriental pied-hornbill, scientifically named Anthracoceros albirostris that belongs to the family Bucerotidae, is a native to Singapore. Their population decreased drastically in the early 1900s mainly due to a loss of habitat from urbanisation and hunting. To propagate the birds for the conservation project, nest boxes specially designed to simulate their natural breeding environment – hollow cavities in tall old trees, were placed on tall trees at designated parts of the island and on Pulau Ubin. In fact, after laying eggs in tree cavities, hornbills exhibit a unique cooperative breeding behavior; the mother seals herself up in the cavity for about three months to take care of her eggs until they hatch. She relies on her life time partner to deliver food to her several times a day through a narrow slit until she leaves the cavity. The nest boxes proved to be a success and played a critical role in increasing the hornbill’s population in Singapore.

Hornbills, sometimes known as King of the Forest, plays an important role in forest ecosystems as seed dispersers and pollinators. The birds use their large horn-like bills, for which they are named after, to break up large fruits for their own consumption. In the process, they provide for smaller birds too and help to scatter seeds. Apart from fruits, hornbills also feed on insects and small animals. Despite the sheer size of their beak, their tongue is very short, too short to swallow food caught at the edge of the beak, so much so that they have to toss food down their throat with an upward jerk of their head.

Video credit: Dr Kelvin

Due to their large beaks, hornbills are sometimes mistaken for toucans and vice versa. However, hornbills and toucans are not related evolutionarily. This is a fine example of convergent evolution. In evolutionary biology, convergent evolution denotes a process whereby non-related organisms, in this case, the hornbills and toucans, independently evolve similar traits as a result of having to adapt to similar environments – the tropical rain forest.

The hornbills (of the Bucerotidae family in the order Coraciformes) live in tropical rainforests in Africa and Asia, while toucans (of the Ramphastidae family in the order Piciformes) reside in Central and South America. Further, they differ in a few anatomical structures. Look closely at their eyes the next time you encounter a hornbill, you will see it has eyelashes that are absent in most other birds, including the toucans. The most striking difference however, is the presence of a distinctive feature called a casque, on top of the beak of hornbills. A hornbill’s casque, smaller on the females than on the males, is an example of sexual dimorphism. Biologists often speculate on the function of the casque, including support (for the huge beak), acoustics (hollow structure functioning as a resonance chamber), sexual attraction and species recognition.

So fascinating are the hornbills that it is small wonder that they are subjects of studies for ecology and conservation biology. One certainly need not take up a module in Biodiversity and Evolution (the MDIS School of Health and Life Sciences offers these modules under its degree programme) to appreciate nature but it certainly helps with understanding of biology and hence learning how to protect these treasures of the natural world.

Reference:

https://www.nparks.gov.sg/mygreenspace/issue-15-vol-4-2012/conservation/hornbills-in-the-lion-city

http://www.wildsingapore.com/wildfacts/vertebrates/birds/albirostris.htm

https://www.mdis.edu.sg/academic-programmes/school-of-life-sciences/bachelor-of-science-hons-biochemistry