Candida auris, drug resistance, and another reason to wash your hands

So you might have heard the two paired terms ‘drug resistant’ and ‘Candida auris’ floating around in the news or on the internet, on articles and stories about people contracting this ‘novel’ fungus in healthcare facilities all over the world. But have you ever stopped to wonder what that actually means? What is Candida auris and why is it so dangerous?

To begin with, C. auris is a species of fungus that grows as yeast under the Candida genus. It is a relatively new species, its first reported appearance inside a 70-year old Japanese woman’s ear canal in 2009, hence the name ‘auris’ (ear in Latin). Since its initial discovery, C. auris infections have been reported in 20 countries all over the world, though the true number is suspected to be a lot higher. C. auris is one of the few species able to cause candidiasis in humans, in which the fungus invades and infects our circulatory and central nervous systems, as well as certain organs like the kidneys, liver and even our eyes. C. auris infections are typically heralded by a fever accompanied by chills that are both resistant to treatment with antibiotics. What sets C. auris apart from most other Candida species is a series of problematic and worrying traits, such as the difficulty of identification, its prevalent outbreaks in healthcare environments and its multiple drug resistance.

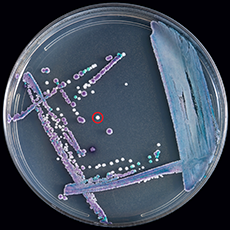

For starters, why is C. auris so difficult to correctly identify? One of the main reasons is its cultures share many similarities to other more common species of Candida, especially C. haemulonii. The standard laboratory testing methods of blood and bodily fluid cultures are unable to differentiate C. auris from other Candida species without specialised technology and equipment such as matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). This can lead to misidentification and eventually, infection mismanagement, placing patients at a great health risk.

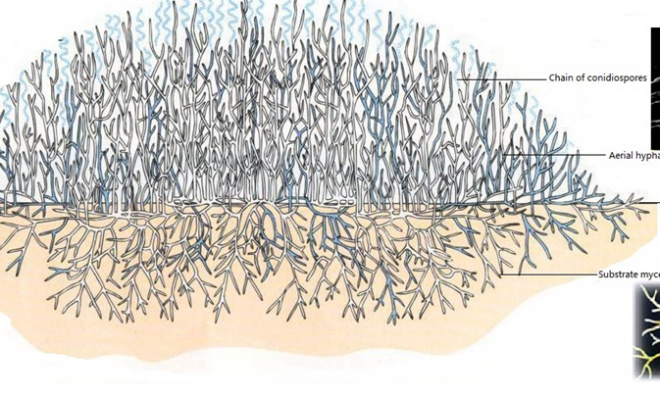

Majority of C. auris infections happen in healthcare facilities such as hospitals and nursing homes, where its risk factors are most prevalent. These factors are similar to that of other Candida infections and include diabetes, compromised immune systems whether due to disease or recent surgical procedures, usage of broad-spectrum antibiotics or antifungals and invasive tubes/lines in the body. In these facilities, the fungus grows on practically any surface, from the handles of doors to our own skin, due to its virulence factors promoting environmental persistence and the ability to colonise on human skin, and is further extrapolated by the alarming infrequency of hand-washing practices in these facilities.

Finally, the most concerning aspect of C. auris is its multiple drug resistance. Recent isolates have been shown to be resistant to the three main classes of antifungals, namely: azoles, polyenes and echinocandins. The only way to treat such infections is to use multiple classes of antifungals all at high doses, though some such as Amphotericin B are expensive, not easily available and tend to also have severe side effects. The limited methods of treatment, combined with its difficulty of identification have made C. auris a dangerous threat in healthcare settings and a hot topic of research amongst the global biological community.

The article is contributed by Wong Ming Li, who is pursuing the Bachelor of Science (Hons) Biotechnology, awarded by Northumbria University, UK